John

Vink

Cambodia-based

photojournalist

John Vink is a native of Belgium. He

has won the Eugene Smith Award for his work on Water in Sahel.

A former member of Agence Vu,

he joined Magnum

Photos in 1993.

Wayne: You have said that your father was a very good amateur

photographer. What memories do you have of his photography?

John:

Did I say very good amateur photographer or good amateur photographer?

Anyhow, he knew very well about all the technicalities, exposure,

filters, depth of field, lenses… He had a Leica,

I think a 3F or a 3G. (I bought one later on and took pictures with it

of the psychiatric ward I managed to get sent to to avoid doing

military service.) But the things my father photographed were the

family, cherry blossoms, mountain ranges and the occasional chamois,

small as a dot against a big mountain slope when we spent our summer

and winter holidays in Switzerland.

Wayne:

You have also attributed your photographic interests in part to the

copies of Life magazine that were kept around the house. What was it

about the magazines that captivated you? What other books and magazines

did your parents keep around the house?

John:

The Life issues were hidden in the cellar (there was no attic in our

house). There was a small storage room opposite the garage with piles

of magazines. I spent hours in there. The first pile of magazines I

came across was National Geographic. Old

issues

from

back

in

the '30s as well. Must

have given me a hint about going to other places.

Behind

that

there

was

a

pile of Life magazine. This was in the late '50s and

early '60s, and my parents who had gone through World War II did not

want their children to be confronted with the war. [David

Douglas]

Duncan’s

pictures of the war in Korea (muddy soldiers sloshing through rice

fields, shell shocked troopers in the cold…) probably motivated my

parents to hide those issues. It was at the height of the Cold War, and

I had bad dreams of Russian planes dropping their atomic bombs on my

head, yet I took the Life issues with Duncan’s pictures up to my room

and looked at them at night with a

torchlight. I also had copies of Popular Science explaining how

to build an atomic shelter…

Even

better

tucked

away

was

a pile of photography magazines with articles

about how to compose a picture, how to take pictures of fireworks and

the like. All topics I wasn’t interested in at all. But surges of

hormones kept me flipping through these photography

magazines anyway, because there was also a chapter on lighting nude

models. I learned a lot about how not to light a subject and about

human (well mostly female) anatomy this way, although the absence of

pubic hair, and in fact the absence of everything (the pictures were

strategically retouched) kept certain questions alive…

Wayne:

What kind of influence did Duncan have on you? Which other

photographers influenced you when you were a young, up and coming

photographer?

John: I can’t say if Duncan

or any other photographer had any direct influence on me. I think it is

more a combination of feelings, encounters with certain images at a

certain moment which molded me over time. I mean, growing up is a slow

process and needs a lot of input from many different origins. It is

never like a thunderbolt hitting me and making me change direction. The

Duncan pictures and the

atmosphere surrounding it at the time, the digestion of all this, maybe

partly explain why years later I never really photographed the paroxysm

of conflict. I am not a war photographer. I am a post-war photographer

and sometimes a pre-war photographer.

I

also

think it is a bit reducing to mention only photographers as an

influence just because you’re a photographer yourself. My artistic

stimulations are varied and relate to music (Arno, Lou Reed, Bob Dylan, Nusrat Fateh

Ali Khan, Swirling Dervishes, J.S. Bach…), painting (Permeke, Saverys, Alechinsky,

Ensor…), and yes,

photography (Larry Clark, [Diane] Arbus,

[Robert]

Frank,

Sergio Larrain,

Graciela

Iturbide …), literature (I was devouring Jack

London as a kid) and certainly comic books with the one and only Hergé, creator of Tintin (maybe this will explain why

I try to have everything in focus)…

There

is

one

photographer,

though,

who at least triggered my desire to become

a photographer. I was 15 or so and probably quite stupid and stubborn

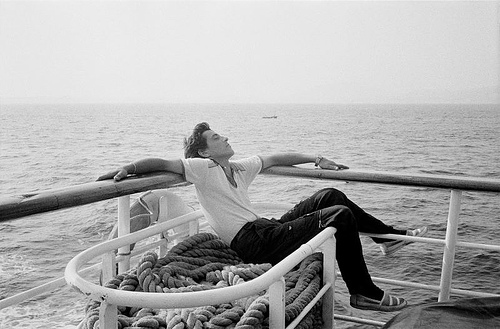

when the “Ye-Ye” period hit France and Belgium. There was a very

popular radio program (no TV at home!) called “Salut Les Copains”,

featuring

a

new

trend

of singers: Johnny Halliday,

Sylvie Vartan,

Françoise Hardy. It was in fact the first successful attempt to

drag

the baby-boomers into consumerism. The success was such that a

magazine, appropriately called “Salut

Les Copains," came on the

market, with pictures of all these stars and starlets of the new

showbiz in France. Most of them were done by a Jean-Marie Perier.

In each issue of the magazine there was an article about “The job you

dream of.” The first issue told you exactly what you should do if you

wanted to become an air hostess. The second issue explained what it

takes to become a photographer. And there was Jean-Marie Periertele-lenses telling the world and credulous me

(happy possessor of a Voïgtlander

Vito CD) in particular how much fun it was to be a photographer and to

approach all those stars. My decision was taken: I wanted to quit

college and become a photographer sitting amid all his cameras.

Wayne: How did you decide to study at

La Cambre? What was you

parents’ reaction to your interest in the visual arts?

John:

My parents weren’t too happy with my decision to quit college and put

heavy pressure (fair enough) on me to finish what I started. It took a

while longer than expected, of course, because after my decision, my

motivation to do that was gone, my mind being focused on becoming a

photographer. But I managed to get through the ordeal. I guess that by

then my parents expected me to have dropped the foolish idea. It turns

out I didn’t, so they thought I might as well get the best weapons to

achieve my goal, and I went to the fine arts university of La Cambre. The concept of La Cambre was in fact copied from the Bauhaus:

a

collection

of

several

interacting visual arts disciplines, ranging

from graphic arts to etching and from sculpture to animated film. Now

this was September 1968! Not the right time if you wanted to study at a

high school or a university, but fantastic if you wanted to fool around

and spend time finding out what you wanted the world to look like. The

guru we had to deal with in the photography department obviously lacked

substance and stature, and basically we were left on our own. I picked

up a lot in other departments, so finally it was a good experience,

even though in the field of photography as a profession I was left

quite helpless. But we had been following a very good class on the

history of photography, and that certainly was where I became aware of

the different worlds photography can take you to and that finally

telling people’s lives, like Dorothea Lange or Gene Smith did, was

something I could relate to.

Wayne: How did you end up initially

photographing theater?

John: In fact, right after La cambre

I started my “career” as a fine arts photographer with these pictures,

got them published in the [Swiss] Camera, and they were exhibited left

and right in an emerging fine art market, and namely at the Jürgen Wilde Galerie in Köln (Germany).

They were the discoverers of Bernd

and

Hilla Becher a little later.

But

after

a couple of years I thought I would be running into a dead end soon,

and the desire of being a photojournalist, which popped up at La Cambre, came back. In those years I

also took these photographs, comforting me somehow in that direction:

But

there

were

no

decent

magazines in Belgium at the time. Only dailies who

would pay ridiculous copyrights (if they even knew what that was). And

I really didn’t know how to move ahead. My former wife, who I met at La

Cambre, was a stage

designer

and that is how I got in contact with the more progressive theaters in

Brussels. I started taking pictures for them and soon ended up doing

things a bit differently than what they expected. I was more taking

pictures of the process of creation than of the play as such, and very

often I was on stage with the actors during the repetitions, showing a

totally different perspective than what the spectator would ever see.

The great thing with theater photography is that you can anticipate the

events: you know that when X says “blablabla,"

that

Y

will

be

staying there, looking in that direction. It really has

helped me tremendously in the all-important issue of finding the right

position, the right distance.

Wayne:

How, in particular then, has music influenced your aesthetic? How has

it influenced your methodology? In the way it affects the way you

structure your coverage and themes?

John:

Music has more of a ‘getting into the mood’ function than a direct

influence on the aesthetics. So it is not directly related to

photography, but it helps me apprehend situations before starting to

photograph or to digest the situations afterwards. Reed to pep me up

and for when I know I’ll have to rock; Waits or “Vier Letzte

Lieder” from Strauss by Jessye

Norman for when I want to isolate on a plane; Swirling Dervishes to

cool down but stay concentrated; Nusrat

Fateh Ali

Khan (the real Sufi stuff, not the “world music” thing) for when I have

to go beyond the real world. I never listen to music while

photographing, of course. I mean, you have to photograph with your ears

as well, so there is no time to listen to music.

Wayne: When you were at Liberation,

you learned to work in a method the photojournalists there called “décalé.” How much

does that method still influence your work?

John: I worked a lot for Libération, but never was “at” Libération, even if Vu

agency [Agence Vu] was a daughter

company of Libération

at its beginning and had its offices in the same building for quite a

while. The initiator of the whole idea was Christian Caujolle, former picture editor at Libération whom I had worked

for a couple of years before he put together Vu agency. Christian,

during his years as a picture editor at Libération

indeed managed to use photojournalism in a way which had rarely been

seen before. It was a matter of looking beyond, to search the edges, to

visually scratch beneath the surface of what’s available at a

journalistic event and come back with images which were relevant and

yet different from what one would expect. It was a matter of creating a

surprise effect, catch the attention and bring the reader to apprehend

the accompanying text with a critical mind. Libération

became known for its unconventional use of photography and this

certainly contributed to the success of the newspaper at the time.

The

same

idea

was

used

by the picture editors at Libération

who were using stock

photographs. Sometimes the results were quite far fetched, or plain

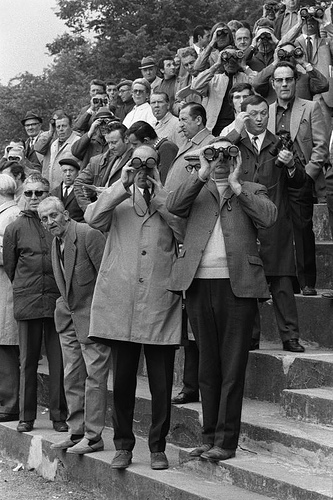

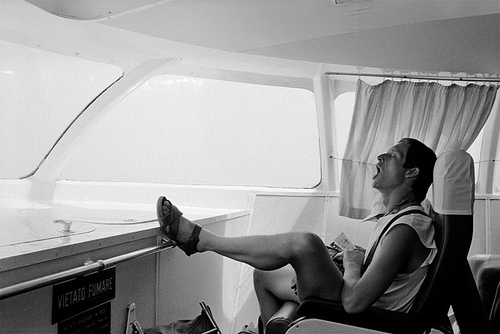

funny. I remember that this picture:

or this picture

(I

don’t

remember exactly which one but I’m sure it’s one of the two): was used

for an article about a survey which found out that the sperm count with

the population in the West was declining…

The

danger

with

“décalé”

is that you could end up using or producing pictures where aesthetic

virtuosity becomes more important than the content. It is something I

always was very cautious not to do, though, and the “décalé” taught me

better where I would and should put my limits in this regard.

But

anyhow,

Christian

Caujolle

thought that the concept he successfully used at Libération

could be expanded and applied to other news media and also to the juicy

market of annual reports or advertisement. So he gathered a bunch of

photographers (Michel Vanden Eeckhoudt, Gérard Uféras,

Pascal Dolémieux,

and

later

Hugues de Wurstemberger…)

around him he had worked with when he was picture editor and founded Vu

agency. It worked fine for quite some time. The line between journalism

and advertisement photography became blurred a bit, but it never really

bothered me because there was enough space for both options within the

agency. For me it was just a matter of drawing the line again as to how

far I would go into the direction of non-journalistic photography, and

that was pretty not far away.

Vu

was very trendy for six or seven years. Then Libération

began to have some difficulties and there were rumors that it would

close its daughter company. So I left Vu end of ‘92 before 15 or so

photographers would be looking for a place to harbour

them and subsequently applied in ‘93 for Magnum. As it turned out I got

into Magnum and Vu is still around. Meanwhile, I had completed the

Water in Sahel and the

Refugees stories.

Wayne: You have talked about your

“need” to leave Belgium. Why was that important for your sense of

mission? For your development as a

photographer?

John:

Belgium is a really interesting place with a rotten climate. It is the

friction line for two strong cultures and has been a battlefield for

every European army (and even a few non-European armies) for many

centuries… It counts an abnormal proportion of creative people doing

things no one else in the world could come up with and counts an even

more important proportion of narrow minded bigots. The food is

fantastic, the beer is the best in the world, quality of life is

probably unequalled, but sometimes I feel this is a cover-up for a lot

of hypocrisy. Belgium is the champion of compromise (maybe that’s why

it is the siege of the European institutions). Belgium is Catholic.

Belgium has a coastline of 60 km. Belgium (the Flemish part at least)

is one village. Belgium is crowded. Belgium is satisfied. Belgium is small. You want to get out of there.

Maybe

if

I

had

stayed

I could have found an equivalent to each and every

story I did in Africa or Asia and dig into Belgium as I’m digging into

Cambodia now. But it turned out different, the itch to to

go out there and see for myself, check things out with a mind as free

and uncluttered as possible was too strong it seems. Things look

crispier, it feels like you grasp what’s going on faster, that you analyze

a situation better when your memory has no references. I think

photojournalism is about knowledge but much more about intuition and

open mindedness.

I

ended

up spending only a couple of months at home each year for several

years. Shall we blame it on National Geographic or on the school’s

atlas with all these incredible names in Siberia or in South America? I

don’t really know. Once you’ve been bitten by the travel bug it’s hard

to settle down. Being away also makes it tough to maintain fulfilling

relationships, so when you come back for some time you find out that

they are not satisfying—and leave again. You get dragged into a spiral.

I did try to settle down a little more after becoming a nominee at

Magnum and even started a documentary photography magazine called

"Themes." I managed to publish five issues, ran out of money and

started travelling again,

working on the mountain people story.

Wayne:

Why has it been so important for you to cover the “powerless and poor?”

Why refugees in particular? From where does that sense of justice and

injustice stem in you?

John: Why do you climb a mountain? Because it’s there.

I must say I never understood why people talk about well-known people.

They have a voice already. So why add more noise? Too much information

becomes noise. I never understood (or rather, wanted to accept) the

fact that all the media focus on the same topic at

the same time. When all the media went to Rwanda, I went to Angola.

World news… What is that? Whose world are we talking about? Do you

really believe the guy in Cambodia who just got kicked out of the shack

he has been living in for the last 10 years gives a 100 riel note about

Israel flattening parts of Beyrouth?

Is

a

Hezbollah

more

important than an Israeli or a Phnom Penh slum

dweller? I guess it depends on where the center of your world is. When

I look at the Cambodian news, Cambodia is in the middle of the map (not

that all Cambodians give a shit about the slum dweller next door mind

you).

I

always understood the function of being a photojournalist as a

go-between, shuttling between one group of people and another to try

and explain how the others are faring. It is a fairly simple job in

fact. You identify a group, go there, look around, sniff around,

listen, take pictures which try to convey what you saw, smelled, heard,

and bring it back to others who don’t have the opportunity of going

there. Personally, as a matter of putting the sound balance right, I

would go to those groups which have more difficulties in having their

voice heard (when the voice is faint it is more interesting for that

exact reason: why is it that faint?). Refugees have less voice than

others. They are pawns. Minorities have less voice. Victims have less

voice. If they had a loud voice (if they were allowed to have a loud

voice) they would not be a victim. Power is about shutting up the voice

of the others. So it goes like this: you have a faint voice, I’ll try

and talk about you. You have a loud voice: I heard you already and I am

not interested in more.

I

guess

it has to do with my parents who taught me to be just, not to cheat,

not to lie, and to shut up when the adults are talking.

Wayne: In

your coverage of the powerless and poor, how fair is it to say that you

often trace the issues back to some sense of the elemental: land and

water for instance? How did you come to that method of covering the

issues?

John:

We may be sophisticated beings, but we still depend on land, water and

air. We are territorially minded. We are dogs pissing on lampposts.

I

did the Water in Sahel story

because—thanks to Sebastiao

Salgado’s

work on the famine in that area in the late ’80s. His pictures were

very strong and moving. They still are. But I wondered why do these

images exist, why did this happen? Sebastiao

was showing us the result, the consequence of something. I tried to

find out why it went that far. The answer was easy to find: no water.

Of course, then it became more complicated: why is there no water? Climate, geography, politics?

I

think I managed to cover only the climate and the geographical or

topographical aspects of the story and only superficially scratched the

political part.

I

said

before: I come after the paroxysm of war. The famine was a paroxysm.

Trying to find out why there was a famine was coming after the

paroxysm. Photographing refugees is coming after a paroxysm.

Photographing the mountain people in Guatemala, Laos and Georgia had

not that much to do with post-paroxysm but a lot with land and

identity. Today I photograph what is happening after the paroxysm of a genocide in Cambodia. And what do

I find (among other things)? Land issues. Maybe I’m not that

open-minded after all…

Wayne:

You talked about how the financial difficulties at Vu helped spur you

to transition to Magnum. What was that transition like? How different

were the two agencies? How has the agency been important to the

furthering of your goals? What are the biggest misconceptions that

outsiders have of Magnum?

John:

As I said, I quit Vu before applying to Magnum, as I thought that was a

clearer position in regard to Vu. I didn’t want to be perceived as a

traitor, so I told Christian Caujolle

beforehand about me leaving Vu and trying to get into Magnum. The risk

was, of course, that Magnum would not take me, in which case I was out

there on my own, because it would have been a bit strange to go back to

Vu. Luckily, it worked out, and I spent the next four years passing

through the required purgatory steps to become a full member of the

Magnum cooperative. I had applied once to Magnum in 1985 already, but

that was way too early, and I was not mature enough at that time.

In

retrospect the Vu episode probably was the best thing that ever

happened to me. It was the biggest move ahead in my “career.” It really

revealed me to the business world in France and also to myself. It gave

me the self-assurance I would need to be accepted by Magnum later on.

The

difference between Vu and Magnum was switching from a small dynamic and

quite iconoclastic place where things were run in a fairly emotional

and messy French way to a much heavier, more complex structure with a

comparatively huge multinational network of offices and agents with

heavy traditions and loaded to the brim with icons. I must say I had a

very hard time adapting (and in fact, after being a full member for 10

years, probably still have not completely adapted). Things have changed

quite a lot these days and nominees are much better taken care of to

find out about the mechanisms of the beast, but at the time I felt kind

of dropped into a big machine without anyone telling me how it would

work. It was up to me to find out.

To

make

things more difficult there were quite violent tensions between the

three main offices at the time, due to cultural differences, personal

histories and because of crippled internal communications (no email).

Although some of those tensions still remain (you can’t rewrite

cultural identity or history) they are definitely less of a burden

today because communications have improved (yes, now we do use email!)

and because if we want to survive we have to get

along and stick together to face the world out there.

In

1994

Magnum was also at a pivotal stage, at the very beginning of a switch

from an analog to a digital distribution. It took ages to implement

this, partly because of our inexperience in that area at the time,

because most members were computer illiterate, except for Carl De Keyzer,

a couple of others and me, because we were early in wanting to do the

switch compared to many other agencies, and because of our specific and

complex way of being organised

which had to be translated into a digital system. Our data management

was written from scratch, tailor made to our needs and has cost us

several tons of money (amongst which 5 percent of our photographers

share, still today). If we hadn’t done that Magnum would not be there

today. It is as simple as that. I think it is the biggest managerial

achievement of the agency ever. We are still free. Freedom is expensive.

The

improvement of the Magnum machine is the thing which helps me most in

achieving my goals, as having an efficient and up-to-date sales tool

brings in better money with which I can continue working on my

projects. But otherwise Magnum never really provided direct support for

any of my projects. I was, for example, very disappointed by the fact

that not one portfolio was published about my refugees work at the time

when there was the exhibition at the Centre National de la Photographie

in Paris in 1994. Not entirely Magnum’s fault, of course, but I was

really expecting the Magnum machine to be more efficient and supportive

for its new nominee at the time. That cold shower made me understand

right from the start that I had to keep relying on my own and not count

on Magnum too much.

As

for

the misconceptions outsiders may have about Magnum? I should know about

what they exactly think first. The biggest misconception I had would

turn around the term “cooperative.” My own (probably romantic) view of

a cooperative is a generous place where ideas, energy and goods are

equally shared in order to produce intellectual and material

improvements for the members. I shouldn’t be romantic, shut my big

mouth and be happy with what I can get.

Wayne:

You said you felt a need to leave Belgium, but what has been the common

thread about where you have lived since you left? In particular, what

is it about Cambodia that has attracted you and compelled you to stay?

John:

The only other place I lived in besides Belgium and Cambodia was Paris

for a few years. Well, sort of… Just like when I was in Belgium I was

home three months a year and travelling

the rest of the time. Now the big difference with today in Phnom Penh

is that I am at home all the time, being somewhere else without having

to travel (and saving a lot of money in travel expenses). Some of the

reasons why I am staying specifically in Cambodia can be found further

down, but not travelling

anymore also gives me the chance to build some serious / normal

relationships.

Wayne:

What has been most pivotal to you in forming your ideas about what

constitutes a story? You mentioned Gene Smith; how, if at all, did he

influence you? From what other art forms have you drawn ideas? How is

multi-media affecting your ideas on this front? What are the limits and

possibilities of multi-media for the still photographer?

John: Before I even knew I would be a photographer or

a photojournalist I was also fed with the books about Tintin.

And

I

guess that these Belgian comic books about a reporter and his dog

having thrilling adventures at the four corners of the world, drawn

with great accuracy by Hergé

in a style called “la ligne claire”

(the clear line) have unconsciously taught me how to construct a story

and what are the elements that keep it together and “entertaining”:

beginning, rhythm,

progression, climax, plot, suspense, end, characters. It also taught me

to try and make pictures with great depth of field.

People

like

Gene

Smith,

Gene

Richards, Gilles Peress,

Larry Towell

and so many other photographers have, in fact, only translated in

photography what I more or less already learned through Tintin about constructing a story.

But

when

I

was

a

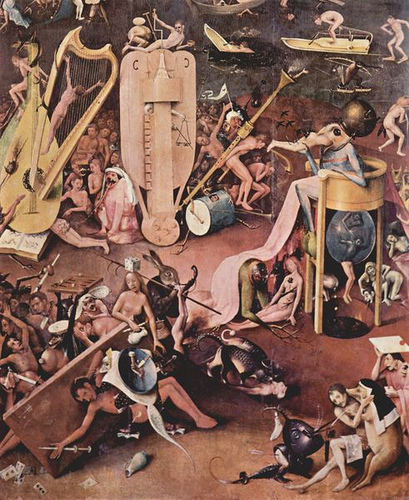

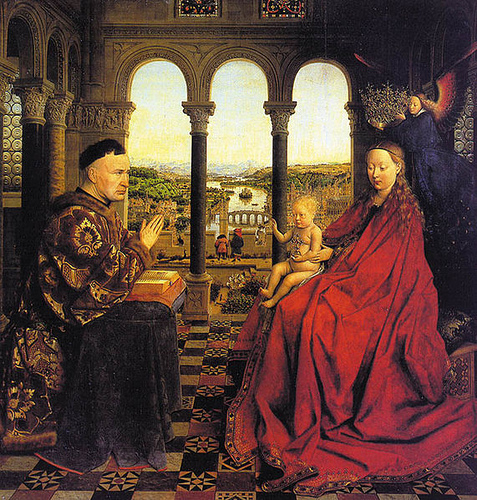

kid my parents also showed me paintings by Pieter Brueghel (here: “The Triumph of

Death”)

Jeroen Bosch (Here: “Hell” from the

tryptich “Garden of

delights”)

Jan

Van Eyck (Here: “Virgin with

the chandelier”)

…and

other

Flemish

painters…

Imagine

what stories you can make up in your

mind as a small kid when you see people being skinned alive in hell?

Later

there

was

Wassily Kandinsky:

Or

Joan Mirò (Woman

Dreaming of Escape. 1945)

That

is

the

power

of

painting: so many stories, so much information,

in

one and only frame.

Photography

usually

needs

more

than

one frame, at least with the kind of

photography I am doing. That is perhaps the limitation / asset of my

photography. It seems that the more I go ahead, the more I have to have

pictures relying on another one, that one picture on its own loses some

of its power if it is not part of a thread. That the thread is what my pictures are about. And

it somehow makes sense as I have been favouring

the story as opposed to anything else for so many years.

To

build that thread is a matter of collecting bits and pieces, left and

right, without apparent immediate connection. It’s like a craftsman

making the pieces of a puzzle he has the concept about but not the

final image. The tricky part is not to forget to collect one piece or

another, as a seemingly unimportant situation may in fact be crucial to

the understanding of other parts of the story. For example during my

first trip to Cambodia in 1989 I completely overlooked the fact that I

had to take pictures of the empty streets of Phnom Penh, of the

twilight just before curfew, of the absence of circulation. In

retrospect it is the most obvious change with today and those pictures

I did not take could have come in handy at one point.

But

you also have to keep an open mind and at the same time be strict and

coherent regarding the concept. You have to adapt the concept in the

light of what you encounter but at the same time keep an eye on the

initial idea. It is only at the very end, when the story is finished

(but is it ever finished?), when you look at the outcome that you start

piecing things together and try to convey and reconcile both what your

initial idea was and what changes you found with the initial idea

during the quest for bits and pieces. I mean: you learn a lot about

things during the collection process, you refined the initial idea and

therefore you have to integrate that in the final result.

With

me the initial idea grows usually out of some other story. It doesn’t

come out of the blue. It’s more of a maze. That’s how I very often end

up working on several stories simultaneously, because suddenly an

interesting situation leads me to initiate a new thread. The decision

to pursue one thread or another and how I do it is probably as far as I

will go in revealing my feelings about a situation. I never use the “I”

word in my stories. The “I” word would only be a distraction.

The

multimedia thing is just a logical extension of the storytelling and is

realistically possible only since a few years thanks to the Internet

and broadband (which I don’t have by the way). It is adding a range of information to the photographs. If

done properly it helps in apprehending.

Wayne:

You use the term “paroxysm” to talk about what draws you to a story.

What do you mean by the word, especially in light of your coverage of

the dislocations to people, especially those relating to the most

elemental (famine and drought, land grabbing), and how powerless and

poor are most affected by those dislocations? Can you also talk about

the concept with regards to your story on Terre Rouge relocation?

John:

I used paroxysm in the sense of crisis, when things go out of hand,

when common rules don’t apply anymore. When things are being

deconstructed, torn apart and when journalists pop up from all over. I

usually come after the paroxysm, the crisis, when things are in

suspension or settle down, when things are being rebuilt, reconstructed.

True

that

the particular case of relocations of people in Cambodia are to be

considered a crisis, but compared to what happened before that in the

country, one can also see it as a (painfull)

part

of

the

reconstruction

of Cambodia as a “normal” country. I

wouldn’t want to sound cynical, but the basic idea I have behind

everything I am doing here in Cambodia is documenting the

reconstruction of the country after the Khmer Rouge regime. What does

it take to recover from near-total destruction, be it infrastructural,

moral, social? Every single

story I am doing on Cambodia can be seen from that perspective. The Terre Rouge relocation

is just one chapter in the Quest for Land, a story about land issues in

Cambodia I am working on, and that in turn is just part of another

story about the reconstruction of Cambodia, just like the several other

stories I am doing evolving around the Khmer Rouge tribunal. Imagine

documenting a country being rebuilt from scratch.

That

is

why

I

stay

here. And that is why I will stay for quite some more

time…

CAMBODIA. Kep

(Kampot). 13/04/2003

|