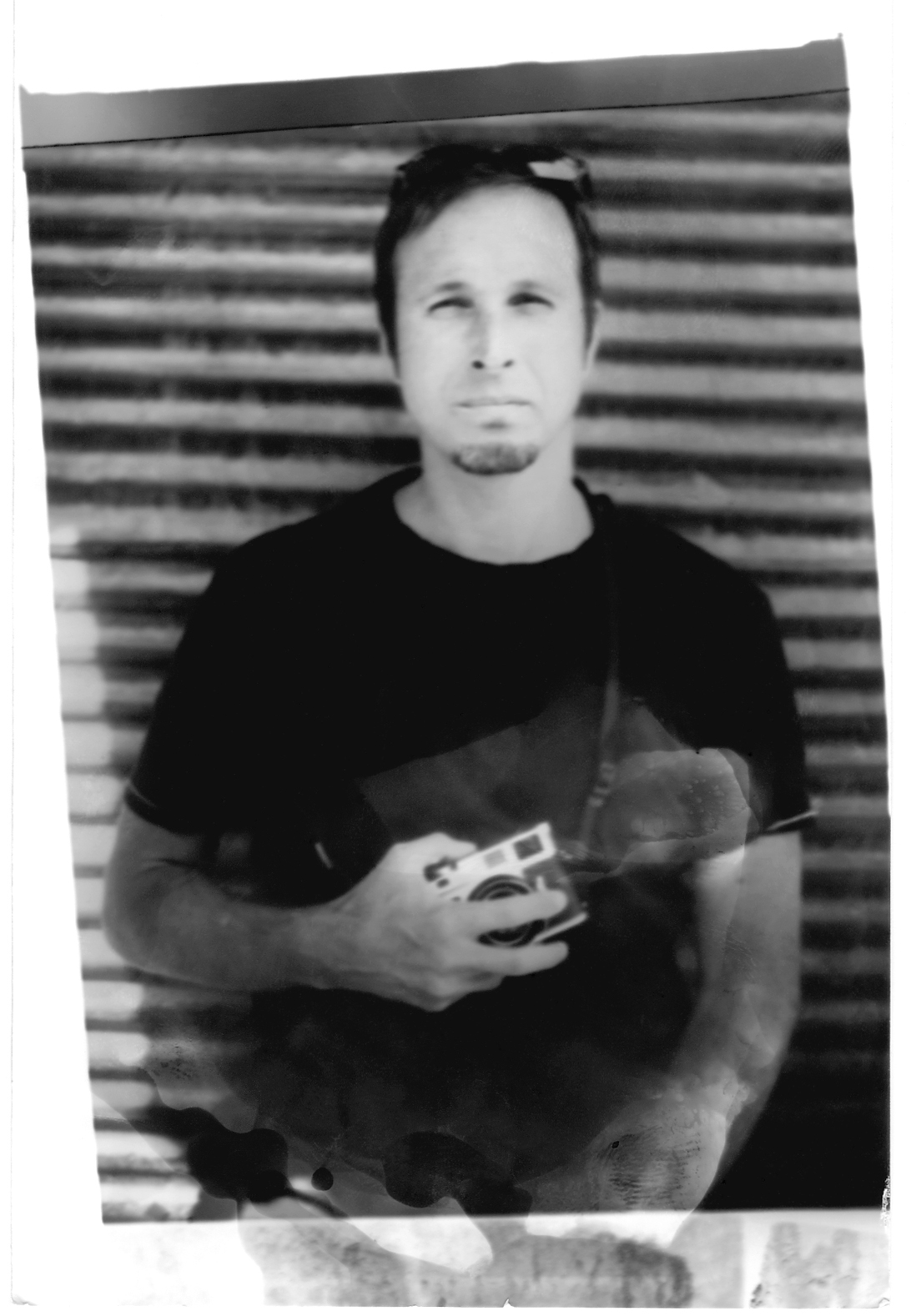

James

Whitlow Delano

Photographer

James

Whitlow Delano has lived in and

documented Asia for more than a decade. He has won the Alfred

Eisenstadt Award (from Columbia

University and Life Magazine), Leica Oskar Barnack, Pictures of the

Year International, Photo District News. Delano's series

on Kabul's drug detox and psychiatric hospital was awarded first place

in the 2008 NPPA Best of Photojournalism competition for Best Picture

Story (large markets). His first monograph book, Empire: Impressions from China (Five Continents

Editions) and work

from Japan Mangaland have been shown at

several Leica Galleries in Europe. Empire was the

first ever one-person show of photography at La Triennale di Milano

Museum of Art in Italy. His second monograph book, I Viaggi di Tiziano Terzani (Vallardi / Longanesi)

was released in Spring

2008. His work has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, National

Geographic Books, GEO, Newsweek, Mother Jones, Time Asia,

Internazionale, Le Monde 2, Vanity Fair Italia and other publications.

Wayne:

How did you stumble onto the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson, and how did

that propel you onto the path of photography? How were Andre Kertesz and Robert Frank

also influential on your development?

James:

This is going back to my beginnings at the University of Colorado. I

was in the university library and bored with studies. I visited a very

kind librarian in the rare books room. She had original prints of

Cartier-Bresson, as I remember it. It was at about the same time I

discovered Frank and Kertesz,

but it would be a couple of years before I would sell my 4x5 camera and

work with Joel Meyerowitz in New York that it

would all begin to take shape. Meyerowitz

is the direct bridge between large format and the Leica.

I was helping him unload Cape Light prints, which had just been

returned ironically from Japan. Japan was not even a real possibility

at the time. Meyerowitz pulled

out this unusual little, quiet camera to make a portrait of an author

who had come to his loft on, I think, 17th Street. It was a Leica M.

What was this camera and why had his manner been completely transfused

with energy? He told me that day that I needed to take a camera onto

the streets. Then the whole thing began to make sense to me.

Cartier-Bresson’s photographs had already penetrated my psyche but now

I began to understand how he had worked. Kertesz’s

elegance and Old World ways seemed, with HCB, some idyll. Robert Frank

showed me that America had its own attitude and that he, a man born

outside the U.S., was able to see things we did not notice or did not

want to see. Later, in Japan and China, I would want to exercise a

similar function. I still do. There were others, but the work of these

three spoke to me on a level that still raises my pulse.

Wayne: You have been based in Japan for more than a decade. What

brought you to the country, and what has kept you there?

James:

I was working in Los Angeles in fashion and celebrity portraiture.

Those days were some of the most carefree and dreamlike in my life:

days in the desert followed by nights in the studio. Still it rang a

little hollow. L.A. can be that way.

To

abbreviate a long-winded story, the idea about living in Japan had been

bounced around and then put down. I then visited a friend living here

and was blown away about how

much more depth the culture had than the mythology actively cultivated

about this country. On that visit, I saw for the first time how I could

make it work and photograph Japan for months on end, deeply without

interruption. I jumped at the opportunity. It was to be for nine

months. It has been for 13 years now.

Wayne: What drew you to covering

places like China and Japan?

James:

Going back to 1993, I had my introduction to Asia through the

Philippines a year before and was then living in Japan. For some odd

reason, Japan did not seem so far but China seemed impossibly far away.

Before coming to Japan, I never thought I would ever travel to China.

It seems kind of odd to see such words on paper now, but it is an

honest recollection.

A

failure to obtain air tickets for Bangkok resulted in my first

life-changing travel to China. It was apparent immediately after

processing film that this place hit me on a very different level.

Wayne: What is it about covering

China’s collision of old and new that the country is seeing?

James:

Well, the exploration of old and new in China was the focus of Empire:

Impressions from China. I have encountered an interesting dilemma

where people relatively new to China, and who have failed to look

carefully at the dates of photographs, sometimes suggest that I am

cherry picking old scenes and dress for that series. Empire was a

series made almost entirely in the 1990s. That was China in the 1990s,

particularly the moment you left any city centre and even more so in

the deep interior. Right around 2001 or so (nothing to do with global

events), I began feeling the

beginning of new era. This newer China work speaks to the awesome

change, pollution, new wealth, gulf between rich and poor. Everything

that happens in China occurs on an awesome scale, whether it be the

massively impressive landscapes,

or the ruination (environmentally), or the transformation of urban

landscapes sometimes done with heavy-handed means. This ongoing series

I call China: Growing Pains.

Such

a

title

might

raise

a

few cackles, a Yank talking about the growing pains

of another country, particularly an ancient one. Actually, I feel

Americans, raised on Manhattan, Las Vegas and Hollywood are uniquely

qualified to sympathize with this period in history in China. We can

understand it. I see so much that reminds me of America. The Three

Gorges Dam could be the Tennessee Valley Authority or the mega-dams out

west. They were made for the same reason: to develop the interior. The

highway building in China, I suspect, echoes our interstate highway

system, which Eisenhower actually built to help the military transport

materiel as much as for 1960s station wagons full of kids. And the

excessive display of wealth is as American as apple pie or trying to

keep ahead of the Jones’s.

Wayne: How does this relate to your

new China desertification project?

James:

Again this echoes the American experience during the painful Dust Bowl

days of the 1930s. There are some frightening differences though. My

university studies, as mentioned, were in Boulder, Colorado, where the high plains of the Dust Bowl meets

the Rockies. The population density in the U.S. at the time was such

that people could and often did move on allowing the land recovered to

the point that grasslands grow there today.

In

Ningxia

and Inner Mongolian provinces where I recently photographed, what were

steppe grasslands 50 years ago are often covered by 100+ meter high

sand dunes. Sand mountains.

Moving sand mountains of tremendous power and weight but delicately

fine, penetrating everything. It resembles the Sahara and there is

little room for people to migrate. China has over one billion people

already.

Mao

Zedong implemented agriculture

policies during the Great Leap Forward in the 1950s

that irreparably damaged grassland that 50 years later look like the

Sahara. This is not an exaggeration. These are massive and global

climate changing growing pains. So, it weaves into that larger project.

Some of the wells have not dried out yet. So there are these tiny

settlements of Mongol farmers

way out in the desert, I found on satellite photographs. Hiring a

motorcycle, I went out to photograph. I don’t know if you are familiar

with the ancient lost Chinese garrison town of Lou Lan in the Lop Nur

area of the Taklamakan Desert

further west. I felt like I was watching the last days of Lou Lan

before it was lost to the world for 2,000 years in these little Mongol

settlements. Staggering. On

those same satellite photographs, oceans of sand go back from the

Yellow River valley for hundreds of kilometres

and connect like sand through hourglass canyons. A moving sand ocean I

photographed that leaps the Yellow River was actually connected to the

sand desert that I photographed several hundred kilometers north in Inner Mongolia. These sand

areas are growing in size.

Wayne:

You once said that: “To observe a society in a snapshot of time can

create a false impression.” You visited China countless numbers of time

while working on Empire: Impressions of China. Why is absorbing a

country in this way so important to the way you work? How do you

compare this working style to those photojournalists who parachute, so

to speak, in and out on assignments?

James:

I have to be careful here. Anyone may photograph anywhere and there

must be a first time for every place. That said, China has an old

saying (well thousands) but one states that one may always fool a

foreigner. Japan and China erect layers of protocol, appearances,

special lavish etiquette especially for visitors. You are not going to

see through most of this unless you invest years in these cultures, and

even still, you must ask yourself, am I seeing what I think I am

seeing? Usually when you ask yourself that question, your sixth sense

is warning you. So, parachuting in

risks falling for cliches,

stereotypes or very skillful visual obfuscation.

There are hundred dollar melons for sale in Japan that have nothing at

all to do with daily life but first time visitors gravitate towards

these aberrations as if they somehow define this country. They don’t.

There

are

a

lot

of

half empty, though impressive, skyscapers

in Shanghai. There is a red carpet

treatment I got there last July in Shanghai and Hangzhou, that I enjoyed mostly because I did not

recognize the country I knew was out there beyond the air conditioned

luxury of my chaffeur-driven

car. My usual mode of transportation are the cigarette smoke filled

local buses with Kung Fu movies that try the sanity, at top volume, on

a TV set that seems to pull the eye in no matter how much one tries to

pretend it does not exist. You know what? I prefer the bus to the car.

Actually I prefer the old buses without TVs and with windows that

opened.

Sometimes

you

should

look

out

from the window of the taxi or bus on that new

elevated highway in Shanghai, Tianjin

or Guangzhou and look into apartments and see how the massive majority

of people still live. China has made tremendous progress but there is a

long way to go. Look into those apartments, and you cannot fail to

admire the strength and sacrifice of families building those massive

office towers that try to steal your attention. The high rises are

important but I care about the 'average Joe.'

Wayne: You are known for traveling

light. On the camera equipment side, you’re said to often carry only a Leica body and a single lens. How

true is that, and how and why did you come to work in this way?

James: I carry two Leica

bodies and film. That is enough weight! I need to be able to move to

work. Life moves too quickly to worry about several cameras hanging

around my neck. I rarely carry the two bodies at the same time. One

body is for 400 film and the

other for 3,200 film at night. So, at any one time I carry one camera,

as I always have in Asia.

Wayne:

Your photographic style has been described as a throwback to another

era. How has that description normally struck you, and how accurate do

you find that viewpoint?

James:

I like a timeless look to work. There is no attempt, overt or covert,

to conjure the past. I think that the subject matter might. I like a

rich print but I will leave it to others to judge if, say my Japan Mangaland

series speaks of another era. Tokyo seems firmly set in the

post-modern, well maybe it is sometimes surreally set in the

post-modern. I work in a manner that involves movement but not that

different than influences mentioned early. So, perhaps that might feed

in part into that perception.

Wayne: Earlier in

your career, you assisted fashion and celebrity photographers such as Annie

Leibowitz. How do we

still see that influence in your work?

James:

Fashion taught me valuable lessons about light, energy, being

aggressive, and quickly capturing expressions that speak loudly in the

images. It also meant interacting with the subject or you got nothing.

They

(fashion

and

celebrity

portraiture)

taught me to get the image, no

excuses and probably no second chances. I owe those lessons to Michel Comte who I worked with in Los Angeles, not

New York. I owe another lesson to a Paul Jasmin,

a gifted photographer and teacher. He talked a lot about “dead eye” in

fashion photographs and portraits. He meant the lifeless look of

someone painfully aware of being watched, on guard. He talked about how

“dead eye” murdered energy and drained life from an image. I have never

forgotten this lesson even when on the street.

Wayne: You noted

that you tend to bring two Leica

bodies with you: one with the ISO set for daylight shooting,

and the other set for an ISO appropriate to night-time shooting. How

systematic are you in seeking your images; how formalistic are you in

setting assignments for yourself? In an essay, you said that you were

not afraid of admitting that you sometimes start with a thesis, so to

speak—something you want to say. Or do you simply like to prowl the

streets night and day, the way Cartier-Bresson was known to do, and let

serendipity do its work?

James:

I am not terribly systematic. It is a matter of reacting to life, not

dictating a subject and wrapping real life around it. In practice,

prowl the streets, as you put it so well. That is what gives me the

greatest joy. I could do that only and be quite happy.

Now

I

have

to

be

clear

in answering your question about the thesis. I

carefully research a subject. It is another aspect of my curiosity. I love

to learn about how people live. Generally, I look for how the powerful

are taking advantage of the rest of us and try to illuminate this. Will

it make a difference? I hope so but I just think someone should do

this. I keep a low profile, especially in China and play the hapless

tourist. I know what I am after. If confronted, which is rare, I

apologize, smile and show respect. Then I move on. Quickly. In this part of the world it is easier to

seek forgiveness than ask permission.

I

have

had to adhere more strictly to a project as the years have progressed.

Westerners like a concise message. Americans in particular seem a bit

obtuse when it comes to nuance. You can imagine how someone making

images in my style would find that a bit frustrating.

Now

here

is the crux of the issue. What I do not like about this is that one

might start this deadly line of thinking, “I will not make this

(amazing) image because it does not fit into my story.” I don’t like to

pontificate, but I will make an exception here. Never, ever,

let

that

thinking

infiltrate

your mind. Make the images, all the images

that speak to you. These images are the important ones for the long

term. The Empire

book is full of such so-called out takes. I personally believe it is

the subtle images that illuminate a culture. Certainly the obvious,

blunt images are less penetrating in this way.

Wayne: How have you become more

conversant with Japanese and other Asian photography after so many

years living there?

James:

I wish I could be more conversant in Japanese photography but it seems

a men’s club like so much else here. Most of the well-known

photographers here seem to be buddies (and they seem mostly to be men).

There is Hosoe Eikoh (last names first) whose

mythical images in the '60s and '70s speak to the Shinto, pre-Buddhist

soul of Japan, and my favorite Moriyama Daido

whose seething, dark energy represents the street smart Japan that I

have come to understand. The clique seems to extend to two of my least

favorite photographers but more famous Pop Culture figures here, Araki

Nobuyoshi and Hiromix. Araki

has positioned himself as some kind of Japanese Mapplethorpe or Helmut

Newton. He’s not.

Forgive

me

for

going

negative

but one need only live here, and thumb through

several of Araki’s uninteresting, wantonly sexually graphic, phone

book-thick chronicles of lovers that he leads kimonoed on the street

through comically nasty scenarios, one after another, after another to

realize that this guy is not doing much here. What is missing, when the

work is viewed outside Japan, are the dime store porn manga

comics as common as stamped out cigarette butts on a Tokyo sidewalk to

realize that this man, with a very good eye, has simply decayed into a

garden variety "oyaji." Taken

in this "oyaji" basically

means perverted uncle. Araki is an "oyaji"

with a good eye. I don’t find his images sexy or even erotic.

Hiromix is a young woman and Araki

hanger-on who photographed, snapshot-style, here dance club life and herself in various teasy,

semi-nude moments in the mirror. I like some of her images where

friends are emerging at dawn from all-night partying but all this gets

old in a hurry and depends very, very heavily on her youthful beauty.

Strip that away, and this heralded work becomes wafer thin.

Moriyama

is

the

greatest

living

Japanese photographer in my opinion, but he is

not alone. There are others who are brilliant, Sugiyama or I think his

name is Shibata Toshio,

who put out a book on the sculptural form of monumental concrete land

reinforcements to protect roads, and seal in rivers, seen throughout

this country.

I

would

like to see more young people’s work, women’s work and more venues for

them. This country has the resources (and the talent) for a more

vigorous photography culture than it has. I know how hard this is to

swallow from the outside but Japan, the land of the SLR, has a quite

small domestic photo world.

Wayne:

How do you explain why Japanese photography and photographers remain

largely unknown in the West (besides a handful of photographers like Hosoe and Moriyama)? Which

photographers in particular would you like to see better known in the

West?

James: If you think Hosoe

or Moriyama are unknown in the West, then

you would be baffled at how unappreciated they are here in their own

homeland. Absolutely baffling.

Araki and Hiromix are

demigods. These brilliant people (Hosoe

and Moriyama) are almost better know

in the West. They seem to show more in New York than in Tokyo.

Wayne:

In what way has living in Asia colored your aesthetic and / or way of

seeing? How much of your outsider status do you lose the longer you

live in Japan, and how is that weakening or strengthening your

photography? What do you want the rest of the world to know about Asia

through your work?

James: Oh man, how can I answer this? I am an

outsider but actually I am not one anymore, as well.

Asia

has

this

mystique.

Rightly so.

It is my home and a real place to me. A Japanese commentator recently

interviewing Wim Wenders, the renown

film director, was genuinely surprised when Wenders

told him that he thought Japan had a strong, unique culture. It

reminded me of Americans saying that there is no American culture.

What? Where there are people, there will be a unique culture but it is

ironic that many people in two of the most iconic cultures on the

planet think that they have nothing defining about their cultures!

I

will

forever be an outsider here, though I live very comfortably here. I

have come to spend one quarter of my life here. Of course, I have a

deep, intimate relationship with Japan. To suggest that the cultures in

this part of the world are forever incomprehensible to foreigners makes

good copy, but I assure you that my Japanese friends find just as many

traits of culture here baffling. They are just normal people getting on

with their lives in a very special place. But how can you embrace the

unique nature of your own country if you have never know

anything else. The longer I live over here in Asia, the more I realize

that people are motivated by the same needs wherever we live. I love

the difference, and at the risk of pounding HCB into a pulp in this

conversation, he seemed deeply saddened in his final days at the

increasing homegeneity of

global culture. He had a point. Tibetans

in

Nikes.

Does that make the world richer culturally? But Nikes may be more

comfortable than heavy yak skin boots. The decision is theirs.

This

knowledge,

gained

from

living

in Asia and drinking in every written

word on the continent I can beg, borrow or steal (or buy on Amazon),

has fortified the work. I depend heavily on visual hints and irony to

those familiar, or unfamiliar, with this part of the world. It is

inseparable. That is why parachuting into a culture can create flat

images.

I

want

people who view images to understand that Asia has all the shades of

grey as anywhere else. I want them not to be starry eyed, or closed

about this continent. It is gritty. It has its problems. It has the strongest,

and most diverse, distinct cultures in a concentrated relatively small

area than any other comparable region in the world. Asia is not a

vacuum. It ties into European culture and has fed it.

The

interface

in

Central

Asia

can be life changing, like a chance encounter

with a girl I met in Ulaa Bataar,

Mongolia with a face that would not bat an eye lash in Tokyo. She could

have been Japanese except for her blue eyes, carrot-topped red hair and

freckles that would impress the Irish.

Likewise

in

an

Urumqi Museum, (Chinese Turkestan), there is a

mummified corpse I saw of a tall Celtic man with sandy coloured hair and a high, long

nose, 3,000 years old, who had inhabited the Taklamakan Desert, now in Chinese Turkestan, before the Turkic Uighur people displaced these

Celtic people in the 8th Century. They are believed to have emigrated

over time into the crossroads region of Afghanistan, Kashmir and

northern India. There was also 3,000-year-old tartan plaid fabric in

this museum preserved by the extremely dessicated

environment of Central Asia. Remember that the Huns that sacked Rome

had originally emigrated out of Mongolia. So, Asia is not this exotic

other-side-of-the-world. It is the navel of the world.

If

one bores of this part of the world, then they have no curiosity. For

the inquisitive, there is no end to inquiry.

|